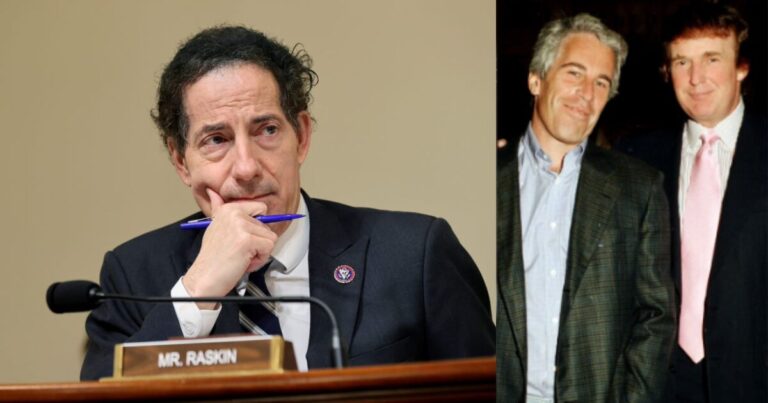

Jamie Raskin, after looking closely at the situation, isn’t holding back: the Justice Department’s way of handling the Epstein files seems more like a cover-up than transparency.

Raskin told reporters he had just come back from a DOJ office that was set up in a remote place — there were only four computers in the room — where members of the Judiciary Committee are being forced to look at documents that were supposed to be released, but they’re under a lot of restrictions.

Congress went there to make sure the Epstein Files Transparency Act was followed, to protect victims, and to expose those responsible.

But what Raskin found was the opposite.

He said there are hundreds of pages where personal information about victims is clearly visible, including their names.

He called this a “big change” from what the law clearly requires. He warned that survivors’ privacy has been broken — either because of terrible mistakes or, as survivors are afraid, because someone is trying to scare others from coming forward.

At the same time, Raskin said the files are full of redactions — parts that are hidden — that seem to cover people who aren’t victims.

Names of “people who helped, supported, or abused others” are blacked out just to avoid “shame, political issues, or disgrace.”

When asked for examples, Raskin gave one that stood out: Les Wexner — someone who has been mentioned elsewhere — was inexplicably redacted.

Even more concerning, he described an email chain between Epstein and Ghislaine Maxwell that talked about conversations between Epstein’s lawyers and Trump’s lawyers during the 2009 case. One part of that email said Trump told Epstein he was a guest at Mar-a-Lago and wasn’t asked to leave. That part was redacted for an unclear reason, said Raskin, and it seems to go against what Trump has said publicly.

Raskin stressed how big the problem is: the DOJ has released 3.5 million documents but is holding back 3 million more.

Members of Congress have only looked at a few of them. He said there’s no way Congress can check these redactions before the Attorney General testifies — especially with only four computers.

His conclusion was clear: “I think the Department of Justice has been in a cover-up mode for many months.”

He said the way forward is to let survivors speak out, hold public hearings, fully release the files, and only allow one kind of redaction: the names of the victims.

He warned that anything else would make the situation even worse.